B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1993

Dip. Ed., (Counselling Psychology), The University of British Columbia, 1994

M.A. (Educational Studies) University of British Columbia, 1997

© Peni Brook, October 1997

ABSTRACT

Concepts of safety as a crucial factor in learning exist as ubiquitous underlying assumptions throughout the literature of Education. What safety is is rarely defined, operationalized, or evaluated however. This may be due in part to a paradox inherent in education that learning may often be simultaneously challenging and exhilarating, confirming and disconfirming, disturbing and transformative for the individual. Nonetheless, an element which is assumed to be essential for learning, but which is perpetuated as an undefined and uninvestigated assumption, is a significant and important area for study.

In this research project, eight adult educators discussed their assumptions about safety and learning, gave examples from their practice which highlighted why safety was a crucial factor, included thoughts about differences between qualities of challenge and threat or fear, and considered ways of improving learning by establishing safety within education programs. Interpretive findings drawn from these interviews were combined with data from the literature to suggest a tentative theoretical model. In the thesis project's concluding discussions, implications for theory and practice are supported by data to suggest that safety is a fundamentally important element in strong and positive learning outcomes.

Research Questions

Choosing a Research Approach

Seeking a Basic Understanding of Safety

A Preliminary Definition of Safety

Purpose of the Thesis

Contribution of the Study

How the Project was Developed

Language of the Thesis

Terminology

Gender Neutrality

Culture

Anticipated Questions

Limitations of the Study

Structure of the Thesis

Outline of Chapters

Chapter Two: Surveying The Literature

Paradox

Confirming and Contradictory Evidence

The Learning Context

Education

Climate: the Social Dimension

Power and Control

Learning Relationships

Teachers

Learners/Learning

Social Dynamic/Group Dynamic

Implicit/explicit process.

Group norms

Processes of Learning

Selected Theories of Learning

Learning to Learn

Risk in Learning

The Role of Safety in Learning

Graphical Representation of Safety in the Learning Context

A Tentative Theoretical Framework

Chapter Three: Research Design and Methodology

Research Framework

Qualitative/Interpretive Approach

Ethnographic Model

Ethnographic Techniques

Pilot Study (Winter 1995)

Role of the Researcher

Participants

Criteria for Selection

Number of participants

Basis for recruitment.

Anecdote: seeking participants.

Who is not included?

Time Commitment of Participants

Ethical Considerations

Letters of Consent to Participants

Guiding Ethic: Research Transparency and Supervision

Participant Feedback

Framework for Data Gathering

Technique: Semi-structured Interviewing

Augmentation: Research Journal

When, Where, & How

Interview Questions and Rationale

The Interviews

Method of Data Transcription, Control, and Storage

Interpretation

Chapter Four: Presentation of Data

Preparing Data

Transcribing Style

Participant Feedback to Transcripts

Introduction of Participants

Blaire: Executive Director, Social Service Education Agency

Dale: Professor, Northern Regional College

Dana: Medical Practitioner, Administrator of Patient Education

Dean: Assistant Director, University Extension

Jan: Administrator, Regional College

Jean: Senior Information Resource Faculty, University

Sam: Director, Community Education

Terry: Corporate Manager - Workplace Training Facilitator

Summary of Interview Format

Abridged Narrative Summaries of the Interviews

Blaire: Executive Director, Social Service Education Agency

Learning how to learn.

Group norms.

Closing the interview.

Dale: Professor, Northern Regional College

Agency: an outcome of safety.

Learning

Challenge, safety, and learning.

Does it matter if process is explicit or implicit?

Dana: Medical Practitioner, Administrator of Patient Education

Learners and learning.

Lack of safety: negative learning.

Explicit or implicit?

Descriptions of former teachers.

Dean: Assistant Director, University Extension

Educator responsibilities

Teacher - learner.

Jan: Administrator, Regional College

The social dynamic.

The social dynamic: failure of the learning group.

Explicit process.

Jean: Senior Information Resource Faculty, University

The remembered teacher.

Anxiety in teaching.

Style differences and learner characteristics.

Screening.

Safety.

Sam: Director, Community Education

Debrief.

The roles of safety and risk in learning.

Safety: content and process.

Techniques for developing safety.

Differentiating between content and process.

Safety as a process issue.

Terry: Corporate Manager - Workplace Training Facilitator

Shared responsibility: educator responsibility and learner responsibility.

Safety.

Explicit process.

Educator responsibility.

Shifting responsibility for safety and learning.

Educator autonomy and accountability

Discussion

Chapter Five: Review of Interview Findings

Findings Relating to the Interview Questions

Participants Backgrounds as a Learners and Educators

Teachers Remembered from the Past

Participants' Concepts of Safety

Social Dynamic/Learning Relationship

Negotiating Group Norms

Comparing Implicit and Explicit Processes

Who is Responsible for the Learning Climate?

"Do you have any questions? What has been left out?

Unexpected Findings

Similarity of Participant Responses to Interview Questions

Learner Characteristics

Style Differences

Responses to style differences.

Dialogue between two basic style types.

Screening

Language: "Not get shot down"

Challenges and Misconceptions

First Challenge: Classrooms are Inherently Safe

Anecdotal examples from discussions about program safety.

Second Challenge: Threat is More Efficacious than Safety

Anecdotal example about threat.

Discussion about threat.

Third Challenge: Too Much Safety Stifles Learning

Fourth Challenge: Safety Cannot be Defined

Anecdote about Defining Safety.

A Story about Misconception

Discussion about Challenges and Misconceptions

Glossary of Terms Drawn from Interviews

Chapter Six: Discussion of Implications

Overview

Tentative Theoretical Framework

Narrative Outline of the Tentative Theoretical Framework

Learning Relationships

Learners.

Educators.

Social dynamic.

Learning Context

Social culture.

Organizational administration

Program planning.

Program planning - evaluation.

Program planning - technological approaches to communication.

Policy.

Policy - sustainability.

Politics.

Politics - power and control.

Politics - democratic process.

Research.

Safety

Understanding Safety

Commonly Held False Ideas About Safety

Operationalizing Safety

How to Establish Safety

Effects from Lack of Safety

Concluding Discussion

A Critical Look at the 'existing social image' of Education

Philosophy Considerations and Moral Leadership

Limitations of this Thesis Project

What is Served by this Project?

My Experience

Doing the project.

Dialogues with strangers.

My point of view.

This is not the end, this is only where I stop.

Postscript

LIST OF FIGURES

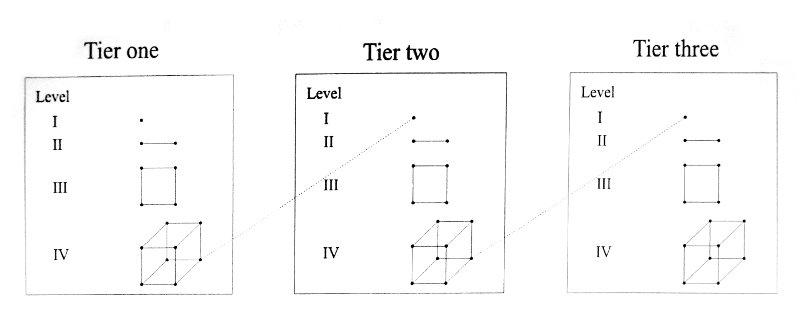

Figure 1: Adaptation of Fischer's (1980) Skill Theory Metaphor for Learning

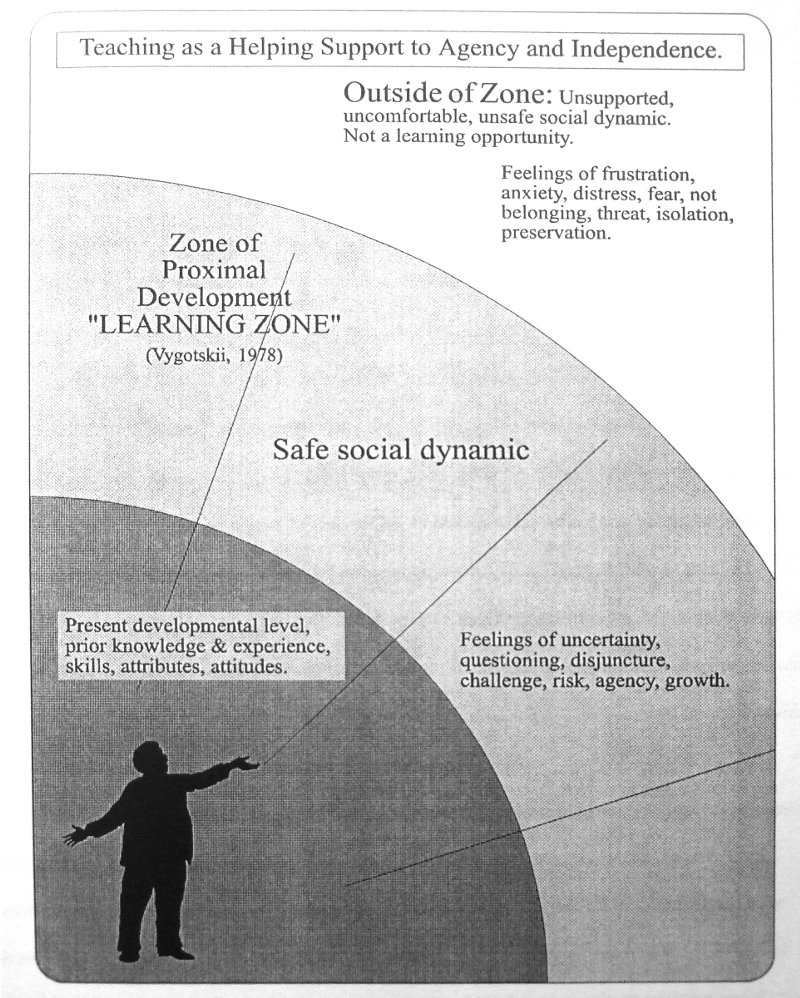

Figure 2: Adaptation of Vygotskii's (1978) Zone of Proximal Development

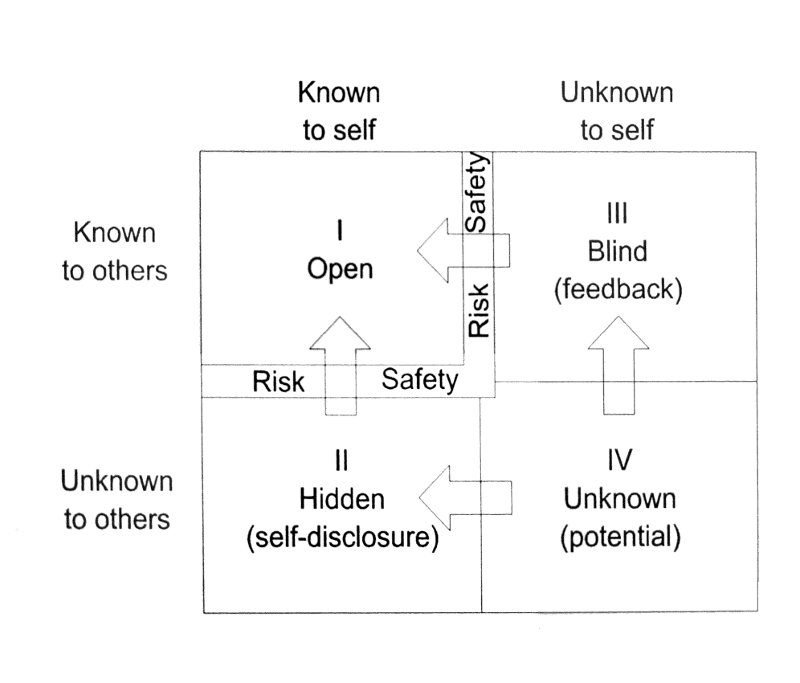

Figure 3: Safety in Learning - an adaptation of Luft's (1984) Johari window

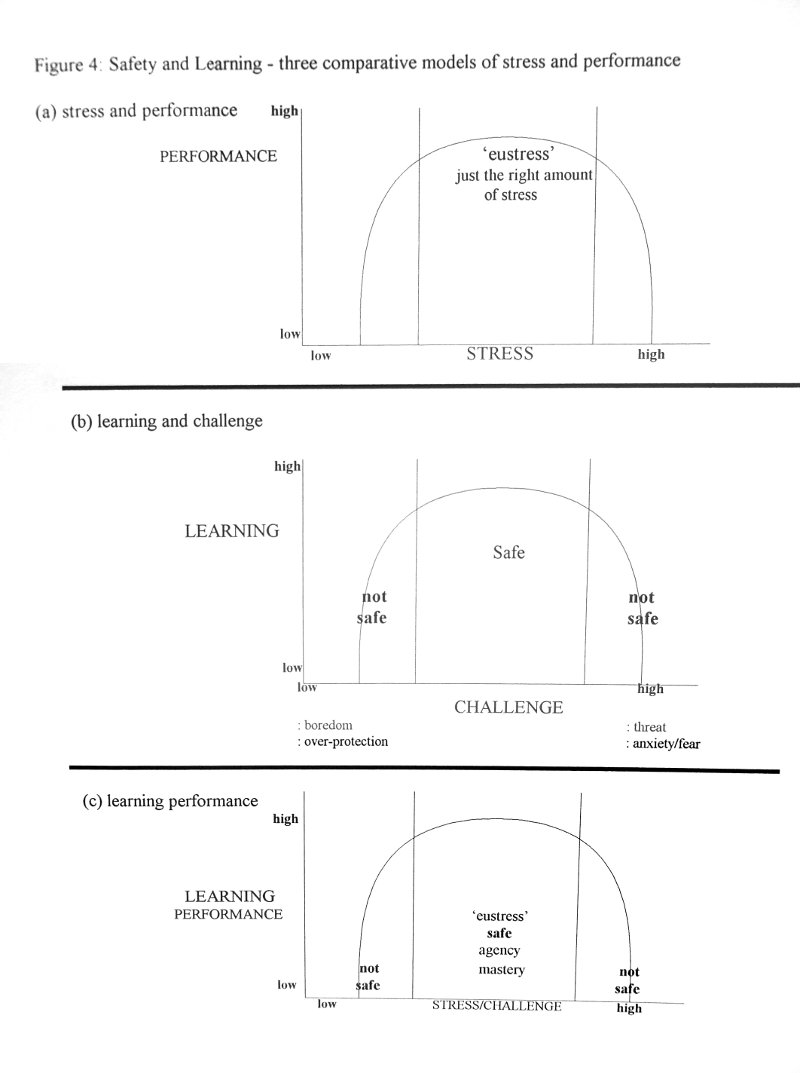

Figure 4: Safety and Learning - three comparative models of stress and performance

Figure 5: Chart of participant responses to interview questions

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My graduate advisor, Dr. W. S. (Bill) Griffith, died unexpectedly in the middle of my program. I missed his acerbic wit, extraordinary critique, and powerful support for my work.

When I was given almost immediate notice that the entire adult education faculty corps declined to serve on my committee, I felt discouraged. I ask that the brief acknowledgments expressed here about individuals (from other program areas) who offered their assistance, be understood as feint reflections of the appreciation I feel.

In one of life's finer turns, Dr Shauna Butterwick was recently selected as an assistant professor for the adult education program area, and has made Bill Griffith's office her own. For two years previous, Shauna had extended to me her informal academic support and methodological guidance. She gave me feedback upon which to think, and the space in which to disagree. Since Shauna did not hold a tenured position at the time, I was surprised and pleased that Dr. Coombs recommended her for my thesis committee. Shauna was a keen critic, generous with her time and her encouragement.

I have considerable experience with engaging different evaluation styles and abilities because the nature of my thirty years of teaching and consulting required critical evaluation of my work. I appreciate feedback. The critique I received from external reader Dr. Anthony (Tony) Clarke was exceptional beyond comparison for its quality of discernment and attention to details.

When Dr. Jerrold R (Jerry) Coombes found that his minor interest in being a third reader on my thesis committee became unaccompanied by other departmental colleagues, he provided a bridge to my program completion by willingly ascending to committee chair. At a time when the project seemed quite vulnerable, Jerry contributed stature, clarity, graciousness, and equanimity.

I first met Dr. B.E.J. (Billie) Housego four years ago as a student in her estimable course on learning. Billie was the first faculty member to support my project and the only one to see it through to the end. Her scholarly knowledge, strength of character, empathy, abiding commitment to graduate student work, and willingness to proofread thesis drafts nourished me well for three years.

Dan Worsley and Joyce Robinson, in the awards and financial aid office, were accessible and respectful as they combined intelligent common sense, forthright compassion, and a mastery of procedures to support my studies with financial information and resources. That their support is extended to all students makes the university feel like a more humane place.

Above all, my academic program has been carried forward through the continual sustenance of caring hard work in daily life provided by Benjamin Damm, Lucas Damm, and Carson Damm, my children.

Learning is the essence of survival and fulfilment. We need to acquire the skills to learn so that we may function, develop, and grow. Learning activities take much organizational, educator, and program participant effort; but often the results seem a great deal less than was hoped. When learning programs are inadequate - for whatever reasons - the costs are high in many ways to individuals and to society. I wanted to identify a key element of learning which might contribute to limited results, and then try to understand the impact on education. I hoped to make a contribution to how we understand the experience of learning, and what it means to teach.

The role of safety in learning was the last thing I considered. My preliminary reviews of the literature, and discussions with educators, investigated several factors such as learning theory, program planning, teacher education, instructional design, social dynamic, and organizational development. During this early study I appreciated many explanations for limited learning results. But remedial changes in these various areas often failed to significantly increase the numbers of learners who succeeded, so it appeared that something fundamental still seemed to be lacking.

As the search for clues continued, I began to notice references to safety and learning. Phrases such as 'once the safe learning climate is developed....[then learning/teaching/education begins]' popped up in books, articles, and conversations without an explanation about what safety meant or by what criteria safety might be recognized. A concept seemed to exist unaccompanied by vocabulary or theory. I retraced the investigative journey and asked a new question within each educational area: what assumptions about safety(1) and learning are present?

I discovered that, although references to the importance of safety seemed to pervade the writings about education and learning, safety was rarely defined. A concept about safety prevailed even though meanings and criteria remained obscure. The assumption that safety somehow plays a key role in learning was ubiquitous yet unexplored (not operationalized, rarely applied, under-evaluated and seldom indexed). As a kind of generic assumption safety seemed overlooked by researchers and undeveloped by practitioners.

Cherryholmes (1988) called such assumptions 'primitives': hidden attitudes, embedded in normative approaches to education, which have remained implicit, crude, and unformed. They are "taken as given and not questioned. They are not defined. Often, they are not mentioned" (p.2). McIntyre (1993) described primitive assumptions as "presuppositions which are in the form of taken-for-granted deeply sedimented meanings...likely not to be philosophically explicit understandings at all" (p. 85). Recognizing safety as a primitive assumption created a dilemma. If safety is a crucial precondition for learning, as the assumptions seem to suggest, how might the effect of safety (or lack of safety) on learning be known? If safety is not explicated, demonstrated, or evaluated, how do we know if safety is an important issue, or if it is even present? Examining assumptions about safety seemed a worthwhile way to seek greater understanding about learning and teaching.

This chapter offers an overview of the research project. First, the research questions are introduced. An introduction to methodology is followed by a brief preliminary description of safety then by a discussion about limitations of and challenges to the study. Finally, an outline of the overall thesis structure provides the guiding framework.

Research Questions

The primary research questions investigated assumptions about safety by asking: (1) what assumptions about safety are common among a select group of educators, (2) what influence do educators perceive safety to have in learning, and (3) by what criteria might safety be recognized? Auxiliary questions sought to extend the substance and relevance of the project by asking: what related prior research has been done; what experiences have the research participants had and, finally, what is implicated when results from prior studies are combined with findings from the interpretation of interview data?

Choosing a Research Approach

I felt that my ability to understand and interpret data would be enhanced if my research framework was consistent with the interdisciplinary and speculative approach I used to arrive at questions about safety assumptions. I sought a methodology capable of transforming my informal interest into a formal research enquiry. I wanted to listen to educators discuss their perspectives, experiences, and concepts, to respond critically as significant data emerged, and to find different ways for interpreting data. I chose an interpretive approach for its ability to explore underlying assumptions by juxtaposing new and existing data in flexible and dynamic ways throughout the project. As I outlined the study, I also sought a basic definition of safety with which to guide the project.

Seeking a Basic Understanding of Safety

Safety may be an easily recognized concept which is not readily explained objectively but needs to be construed interpersonally. Brennan (1977) calls concepts like safety 'open-textured' because although there are specific ways of recognizing what is (or what is not) a safe experience, one cannot generalize to a given set of criteria capable of identifying cases in which safety is present or absent. Rationales for safety can be recognized, however, and can provide a broad standard for adequately judging what will or will not 'count' as safety. These rationales may always be incomplete because they need to be fundamentally sensitive to contextual changes. Therefore criteria for defining, establishing, and evaluating safety may need to be negotiated within each context, according to broad rationales about purpose and effect.

The first challenge of the project was how to describe safety well enough to explain the meaning and purpose of the study while maintaining an open design capable of discovering authentic data which might not be obvious at first. When I started the project, I began to frame the assumptions I encountered in the literature as open-ended questions for colleagues, without attaching any definitions of safety. I thought I was offering an open process which would encourage others to talk through their concepts, uninfluenced by any assumptions I might have.

However, many of those with whom I spoke at first needed more of a basis for discussion. Because I began the study looking for answers, I felt uncomfortable defining safety outside of my own contexts and relationships. I felt caught between two conflicting demands: to explicate safety conceptually in order to draw many people into the discussion and, at the same time, to create an open dialogic climate which allowed concepts about safety and learning to be revealed as a product of the study.

Another dilemma about giving an introductory definition for safety was my valuing uncertainty as the basis of an interpretive study. Griffin (1987) explains how conceptually open research might be of value because it can be "useful to others...who may want to: (1) broaden their ideas of what is possible to experience; (2) find words to express what they have experienced; or (3) find the courage to say 'no, that is not what I have experienced. For me it has been different.' " (p. 210). I decided to try bridging uncertainty and form by defining safety well enough and broadly enough to provide others with an introductory framework; I hoped that my views would do not get in the way of their thinking about safety from their own perspectives.

A Preliminary Definition of Safety

Standard meanings of safety were taken colloquially in terms of what is present in and what is absent from an event. Safety means protection, the absence of threat, and the freedom from the danger or anxiety of harm, loss, damage, or trauma. General meanings of safety might be understood inter-culturally, but safety may be a personal experience stimulated by situational factors and individual perceptions or feelings.

Attempting to find universal guidelines for effective teaching practice, Vella (1994) drew on forty years of teaching in North America, Africa, Asia, South America, and the Middle East to construct a framework of twelve principles for stimulating learning. Vella's principles include organizational and relational approaches to subject matter instruction. Safety is the second principle and is, according to Vella, "linked to respect...it means that the design of learning tasks, the atmosphere in the room, and the very design of small groups and materials convey to the adult learners that this experience will work for them. Safety does not obviate the natural challenge of learning new concepts, skills, or attitudes. Safety does not take away any of the hard work involved in learning... Safety is a principle that guides the teacher's hand throughout the planning, during the needs assessment, in the first moments of the course (p. 6)."

Personal agency and capability imply a sense of personal control, empowerment, and usefulness.

Safety might be an umbrella concept if several elements of relationship and learning(2) are interconnected in significant ways (Calkins, 1986; Svinicki, 1989; Short, 1990). The possibility that safety issues may underscore many aspects of learning increases the importance of clarifying what safety is. Perhaps identifying the effects of safety might provide useful information with which to clarify what safety means to learners as well as to develop criteria for creating, adjusting, and evaluating safety within learning groups.

As a principle by which to foster a climate in which learners feel capable, safety may not be explicable in the normative sense. Individuals may recognize what safety means to them in a given situation, be able to share meanings with others, and find ways to negotiate the development of safe relations within a group, and still, consistent with Brennan's description of open-textured concepts, feel it inappropriate to define the meaning of safety in fixed or generalizable terms.

Norms for defining safety and for developing a safe learning climate can be explicitly negotiated once shared understandings are reached. Communicating differences and probing similarities can clarify perceptions and meanings so that agreements about relationship may be achieved within dialogue. Negotiating and developing criteria for safety become key aspects of the responsive, situational construction of meaning (Burbules, 1993; Chevalier, 1995).

In summary, safety' is a broadly used word, but common usage hides a general lack of understanding about what safety means. People recognize cross-culturally that they have similar personal meanings, feelings, and perspectives about safety, and are also able to realize that experiences of safety may differ from person to person. At the same time, social norms do not usually include protocols for establishing a safe climate among individuals. References to the importance of safety pervade the literature on learning and teaching, in the form of statements like: 'once a safe environment is established, then....' but fails to identify, describe, establish, or evaluate what that 'safe environment' might look like.

Early in the study I looked at how safety concepts are used in other contexts. Terms such as workplace or occupational safety, traffic safety, health safety, water safety, and safe sex have become familiar expressions and have been operationalized within various social activities. As one way to appraise the study for face validity I considered how meanings associated with these terms were compatible with or contradictory to the idea of safety in learning. No conflicting differences in meaning or usage were apparent, so I accepted that the underlying meanings which I was attributing to safety were compatible, or at least not contradictory.

As I considered how to accomplish the goals of my study, I rejected several good leads for research. Three examples illustrate potentially useful areas of future research different from what I chose to do: (1) a study which might inform our understanding about safety could investigate what it is about a trusting relationship which feels safe; (2) a search for what is safe in a situation where people are learning really well might yield more information about the role of safety in learning; and, (3) accountability-based research, although neither an element of the meaning of safety nor a criterion for determining safety, may contribute data about what sorts of resources contribute to making the learning context safe. These specific issues could not be fully explored in a preliminary research study such as mine because I needed to maintain a focus on identifying the broad basic issues underlying questions about safety. But the potential for safety to be recognized as an umbrella term added incentive to developing the project.

Purpose of the Thesis

The predominant purpose of the thesis project was to identify assumptions about the role of safety in learning, explicate related elements, and consider implications. Studying safety as an issue for the learning context seemed to be a new and important approach towards understanding teacher-learner relationships. A second purpose of the project was therefore to raise questions about the elements of safety which are crucial to learning, hoping to generate sufficient evidence with which to stimulate robust and provocative discussion among educators in practice and research. The overall purposes are recognition, explication, and understanding of the meaning of safety within learning contexts.

Contribution of the Study

The subliminal influences exerted by hidden assumptions are difficult to identify and analyze. Explicated assumptions can be evaluated and adapted. But if an implicit idea is established in practice, the lack of accessibility to the underlying rationales behind the idea becomes problematic because the idea has power without accountability. The relationship between power and accountability - and safety - resonated throughout the project. The first contribution of the study was to recognize and broadcast the fact that 'primitive' implicit assumptions about the role of safety in learning exist in education.

The project made a second contribution by gathering evidence, in the form of information about safety and learning, from several sources: first, relevant findings from a survey of previous interdisciplinary research were collated; second, interview data were gathered. Finally, when data from both endeavours generated new questions, additional material was drawn from the literature in response. This process created a strong combined data base with which to support a discussion of implications.

A third contribution was the project's responsiveness to the invitation made by Sincoff and Sternberg (1989) on behalf of the ecology of learning. They asked educators to consider the effect of learning contexts on mental activities associated with significant learning. They called upon researchers to "go beyond simply pointing out the necessity of considering contextual influences. They must pinpoint precisely the contextual factors affecting development and the way these factors alter mental activity (p. 50)."

Davis & Sumara (1997) suggested further that "educational theories and practices that are inattentive to the particularities of context and, more specifically, that are inattentive to the evolving relations among such particularities, are no longer adequate" (p. 120). Issues of safety must be at the heart of research into contextual factors and evolving relationships.

How the Project was Developed

My original goal was limited. In the early stages of the project I intended to do only a critical literature survey about assumptions which theorists and practitioners held about safety and learning. I thought that, once the meaning of safety was clarified through the literature search, I could identify useful safety-based implications aimed at improving learning results. I began by surveying issues of content delivery and acquisition and then, when too many questions remained, broadened the focus of my studies to consider the patterns of learning, stages of learning, and techniques which facilitate learning. I conceptualized learning as changes in attitudes, skills, abilities, or responses based on some kind of experience(3). I framed education as learning which is achieved by organizing and managing experiences. Formal education adds an educator-learner relationship and an organizational context to the learning experience. I became interested in the ecology of education when I realized how much of a social experience the learning which occurs in formal education systems is.

Initially, when the early literature search focused on the social context of learning, I envisioned the project as a comparative theoretical analysis of the work of Vygotskii (1978), Maslow (1968), and Fischer (1980). The research of Vygotskii, Maslow, and Fischer linked the social or group dynamic with learning, and raised questions about communicative norms for dialogue, and issues of responsibility. I hoped that an analysis of the literature could identify, evaluate, and operationalize concepts associated with safety in learning in order to suggest a tentative working framework.

Within these selected theories of learning I explored the nature of learning as a dynamic interplay between elements of safety and risk, a relationship which might affect the development of learner agency. Tracing elements of risk, change, and challenge as being inherent in the learning experience, my attention returned to the importance of a safe social climate.

I discussed my preliminary literature findings with academic colleagues and realized that, given the complexity of the issues and the open-textured nature of the concepts, an analytical survey of interdisciplinary research might not provide them with enough evidence to accept the implications as credible. The importance of safety to the theory and practice of education needed to be established with a stronger combination of data than a literature review alone might provide. I decided to conduct an empirical study. While I drew some quantitative data from studies cited in the literature search, I chose an interpretive methodology because I wanted educators to speak for themselves so that other educators might hear.

Language of the Thesis

Early in the project I regarded language choices as key elements of the interpretive process. They would help me articulate the strategies with which to seek common ground among participants about the learning context, while keeping differences from blurring.

Terminology

Some terminology was used interchangeably throughout this thesis. For example, educators were called teachers, instructors, trainers, and facilitators(4); learners were referred to as participants, students, and clients. Programs were also labeled courses, curricula, classes, and learning events. 'Education', as understood throughout the project, was taken to occur in educational settings, which in turn were referred to as school, corporate or workplace training, learning contexts, and centres(5).

Gender Neutrality

The study is about assumptions and concepts educators have about their work and what experiences count as typical examples. The language of gender became problematic in this project. I found the practice of inter-chapter gender switching, or the current research use of the blended pronoun 'he/she', somewhat awkward. I felt that gender neutrality was a more suitable approach for this study because I strove to focus the presentation of findings on the conceptual and exemplar data as much as possible. When referring to participants I favoured two strategies for observing gender neutrality: first, by writing neutrally and, secondly, by using plural rather than singular pronouns whenever I could. My decision to remove gender from the descriptions of study participants elicited an occasional query from individual faculty who, from their perspective, were concerned that gender neutrality might weaken data integrity.

Several considerations were important to me: first, data integrity; second, honouring confidentiality of participants; and third, encouraging critical thinking within readers. Even so, some readers seemed to impose an issue of gender on the study. For example, they wanted to know who among participants were male and female - as though such information would change the data. And, when they attached gender on the basis of how they read the data, the incorrect gender was often assigned. When I questioned participants, none felt that gender should be identified and Sam was most clear about expressing that, while in the immediate culture there are many gender issues which are about the safety of individuals, safety is not fundamentally a gender issue.

As I worked through the interview data I felt not only that identifying the gender of participants might jeopardize confidentiality but also might interfere with data interpretation(6). Gender neutrality in this study sustained reader focus on issues of explicating the basic meanings and experiences associated with safety and learning. Confidentiality of participants was honoured. I am aware of the passionately felt debates among some qualitative researchers about the importance of gender in research. For another kind of study, I might have chosen to highlight gender differences, but for this study gender neutrality seemed the most appropriate way to respect the data and the participants.

Culture

I have used the term 'culture' throughout the project to represent the social dynamic as it has been developed or learned by group members. 'Dynamic' is the way participants react to each other - over time establishing the distinctive patterns or norms which characterize the group culture. The transformation of participants from a group of individuals dynamically interacting into a group culture is the site of the safety discussions which form the basis for this project. A group culture will develop, whether guided according to negotiated values, or arising spontaneously out of haphazard interpersonal connections.

Within the broad sense of group culture, 'differences' among participants will always be a challenge to represent in research. Intracultural differences are significant to the social dynamics and dialogic relationships. At the same time, cultural differences can be transparent, transformative, catalytic, insignificant, crucial, or distorting. I sense that insofar as the development of a safe climate is concerned, it may be the relational attributes of participants and the quality of dialogue (not the educational setting, personal preferences, or cultural biographies of participants) which most strongly influence the depth, complexity, and benefit of group development discourse. The study is concerned with the culture of learning and these communicative issues replay throughout the project. I focused on the cultivation of the social dynamic because I felt that that approach best respected and represented the data and the participants. The preliminary design stage of the project uncovered several secondary questions which could be anticipated in the process of refining the methodology, as well as some inherent limitations which could be acknowledged early in the study.

Anticipated Questions

The preliminary literature search identified several elements of context, and generated, in addition to the fundamental questions about safety and learning which structure the project, many questions which relate to group processes. Some of these questions were anticipated and embedded within the interview questions: what is the influence of the group dynamic, how is safety experienced in the group dynamic, does it matter whether or not the norms of group process are implicitly or explicitly known, how are risk and challenge related to learning, and if safety plays a role in learning, who is responsible for the safety within the group dynamic?

As the study progressed, other questions emerged such as about learner responses to risk and challenge. I wondered about the importance of participants being aware (attention) and feeling a confident commitment (agency) throughout learning process. Accepting that awareness and confidence were significant aspects of learning, I asked about possible connections between a felt state of agency(7)(7) and feelings of challenge (as different from feelings of threat) about learning. The literature identified agency as a key factor in learning achievement, motivation, persistence, and participation so I expected issues of agency to emerge from the data. I was curious to discover how agency, safety, risk, and challenge might be (or not) related.

Limitations of the Study

Although the concluding chapter of the thesis discusses limitations of the study which became obvious during the research, some limitations were either inherent in the design or raised as concerns before the study began. Limitations embedded in the framework ranged from participant selection to data analysis - because the study focused on the broad perceptions and practices of adult educators about the role of safety in learning, not on the attitudes of their learners. Educator responses were expected to yield data about both learning and teaching because educators are also experienced learners themselves.

Giving issues related to safety a highlighted attention seemed to diminish the importance of other crucial issues. This natural effect of a research project needs to be kept in perspective. There is no suggestion that safety is the only crucial issue, only that it is the focus of the study.

Many important areas of research were omitted for practical reasons, and I would like to mention two - for their potential future importance. First, research concerning issues of safety and how children learn was excluded from the study because of developmental characteristics of that population and the time constraints of the researcher. And second, major psychological conditions which may also relate to safety and which affect learning were also not included. For example, I excluded the research on psychopaths, a group of learners known to be very low in their relational safety needs and high in their abilities to learn ( Hare, 1993). I also omitted studies about people who suffer so much post traumatic stress that their safety needs have become inordinately high and their ability to learn become permanently compromised. Other studies which analyze these groups could yield rich data and generate new hypotheses.

The absence of a quantitative bank of findings may be seen as a project limitation. I felt that an interpretive study offered a particularly sensitive and reliable approach to exploring basic assumptions about safety and learning. Although quantitative experiments offer 'objectively' measured and valid data with which to generate useful theory, they may have particularly problematic aspects when applied to the culture of education, and be vulnerable to discreditation by contrary findings. Interpretive data, however, retain an enduring credibility, based as they are on experience and perception. One may disagree with the interpretation of a person's lived experience and one may reinterpret findings; but one cannot discredit the experience as it was felt. I hoped that, by the concluding chapter, the thesis might blend quantitative and interpretive data into evidence capable of supporting the concluding discussions about implications.

Structure of the Thesis

The research was conducted in layers ranging from the informal pursuit of ideas about learning, through a review of research literature, to a study of attitudes held by other educators. Thesis structure reflects that process, including the interpretation of the data, from which implications were drawn and is outlined in the following summary.

Outline of Chapters

Chapter Two summarizes literature research from three basic perspectives. First, an

introduction to paradoxical concepts in education is followed by a discussion of confirming and contradictory evidence. Second, information about the nature of the learning context focuses on what education is understood to be, what are the social dimensions of the learning climate, and how issues of sustainability, power, and control affect the development of the social context. Third, learning relationships between educators and learners, and among learner participants, are explored in terms of processes for negotiating the group norms which characterize each learning culture. Fourth, the processes of learning are considered within a framework founded on a selected group of learning theories which include the work of Vygotskii, Maslow, and Fischer. An emphasis is maintained on learning as a social transaction which works purposively to optimize the abilities, resources, and personal characteristics of participants. A discussion about the 'learning how to learn' approach to education, and the dynamic factors of risk and safety, round out the literature survey. A tentative theoretical framework, taken from a collection of European research, is introduced.

Chapter Three describes the interpretive research design and methodology used to organize the project. Aspects of critical ethnographic theory which strengthen the capacity of the study to explore several dimensions of the research question are introduced. A pilot study is summarized in which the research question, choice of methodology, structure of the interview, various interview questions, and initial data analysis techniques were tested. An evaluation of the pilot study, supervised by research faculty(8), contributed to the development of the current study design. Precautionary notes about the role of the researcher preface a general description of selection criteria for study participants: the number, rationales for specific selection criteria, the mode for contacting participants, the anticipated time contribution participants make, and protocols for participant feedback. The methods used for gathering the data are detailed as guided by the design framework. The rationales behind the interview questions are included; and methods for transcribing, ordering, and storing the data are outlined. Ethical considerations are also discussed.

Chapter Four presents the data gathered in the interviews. A distilled review outlines data presentation methods, introduces participants, and describes interview settings. Interview data are offered in a narrative form, which strives to be as parsimonious as possible while retaining the key points and unique flavour of each interview.

Chapter Five organizes findings in three ways: those emerging directly from the research questions, unexpected findings, and a tangential discussion about the challenges to and misconceptions about safety which were dealt with during the project. Findings are interpreted within the framework of the interview questions. The chapter is supported by an introductory chart of answers to the research questions and a summative glossary of terms drawn from the interviews.

Chapter Six begins with a tentative theoretical framework constructed of integrated research findings drawn from the thesis project. The derived model provides a basis for the discussion of implications, presented according to the strength of the data. First, the efficacy and application of the theoretical model is structured in three sections which parallel the areas of investigation during the literature searches: 1) learning relationships, 2) the learning context, and 3) research issues. Second, findings specifically about safety issues are summarized. The concluding discussion includes a critical look at the 'social image' of education, reviews limitations and contributions of the study, and offers personal notes about what the experience of doing the thesis has meant to me.

Illustrative figures were included throughout the thesis in response to issues of style differences which were highlighted during the study. The project hoped to offer different types of learners access to understanding the key points of the research as they developed, so the figures were designed to be visual learning aids only, not empirical presentations of data. The reader is encouraged to use the thesis in whichever way works best. The text conveys all the information included in the figures. If the text is confusing, hopefully the figures will help. If the figures are confusing, pass over them.

Defensible educational thought must take account of four commonplaces of equal rank: the learner, the teacher, the milieu, and the subject matter(9).

Literature data about the role of safety in learning(10) are paradoxically rich and abundant on one hand, and elusive on the other. The literature ubiquitously presumes safety to be a crucial precondition for learning, yet on closer scrutiny safety remains almost hidden from research and application, an example of the sort of 'primitive' assumption described in Chapter One. Educators who share the assumption about the importance of safety are given little direction about how to recognize what counts as safety or how to evaluate the effects of safety. The lack of awareness, understanding, or evaluation which results from such unexamined assumptions inhibits the development of a working framework, theory, or field of practice (Kuhn, 1970; Cherryholmes, 1988; McIntyre, 1993; McLaren, 1995).

The initial literature review revealed that many of the terms(11) frequently used during discussions about safety and learning are vaguely defined and weakly understood. The task of Chapter Two was to identify and analyze concepts about teaching and learning until the parameters of the project were established, and then to investigate issues raised within the guidelines of the research questions. This entailed sorting through confusing details, identifying conceptual relationships, constructing temporary theoretical frameworks in order to test the strength of the relationships, and frequently abandoning one line of research for another.

Most of the data found through the first literature search are absent. The novelty of the project demanded layers of clarification and often one set of issues was subsumed by other more comprehensive issues. Chapter Two is not intended to present a summary of the literature I explored, but is a focused reporting of key literature data intended to prepare readers for the presentation of interview findings and the discussion of implications.

Three areas of exploration were suggested by the research questions: (1) the culture and atmosphere of the learning context; (2) influences of teacher-learner relationships on teaching and learning; and (3) processes of learning for and among learners. Selected theories of learning were introduced as ways to understand how the elements related to safety may affect how people learn.

The literature search sought to clarify which new questions were significant to the study by working from general information to particular effects in practice in the continually circular way typical of interpretive research.

The literature search was ongoing throughout the project. Data presented in this chapter are those which seemed most relevant to the interview questions. The focus is such that information found at the beginning of the study is combined with findings emergent towards the end, so readers may know early in the thesis what data are brought forward to the concluding discussion of implications.

The first step in finding direction for the project was to recognize that ideas about learning programs seemed to be confused by paradox. The concept of paradox may partially explain why assumptions about safety and learning remain simultaneously ubiquitous and unexplored. The existence of paradoxical relationships among the concepts studied often confounded the study because issues related to safety seemed fragmented from the broad discussion about learning. Paradoxical and disparate aspects of safety identified by this project were: the effect of power and control in relational communication, the development of the group dynamic in a hierarchical social structure, differences between implicit and explicit process, and the relationship between risk or challenge and a safe learning climate. Paradox is discussed in conjunction with what sorts of evidence can support an understanding of assumptions.

Paradox

Paradoxes seem to be simultaneously confusing and informative; informative in the sense that intuitively congruent patterns can be identified and accepted, but confusing because the pieces which construct the patterns often do not seem to logically fit together. Paradoxes may be reasonable and well-founded descriptions about seemingly incompatible facts which, when linked, form cohesive ideas; they can alert us that paradigms may be reconfiguring by successfully juxtaposing seemingly incongruous realities. Jarvis (1992) suggests that learning can be best understood as a collective of paradoxes.

Our understandings of both learning and safety seem to be embedded in paradoxes which might be expressed as follows: learning as a process is frequently discussed but rarely defined or analysed; learning as a tangible outcome continues to be evaluated even though learning has never been conclusively defined; and, learning occurs within individuals, but usually while individuals are within a social dynamic. The broadest paradox associated with safety is that some educators still suggest that threat, not safety, may be the effective catalyst for learning while the idea that an unsafe climate might constrict learning potential intuitively makes sense.

Paradoxes alert us to the possibility that our understanding of the elements which form the paradox may be limited, not that the data represented by paradox are problematic. The struggle to find clarity in a study defined by paradox was served as much by a search for contradictory evidence as for confirming.

Confirming and Contradictory Evidence

When paradox is found at the heart of a study, a search for disconfirming evidence may illuminate issues more usefully than may an investigation which focuses on consolidating or confirming particular clusters of data. The ongoing tensions between confirming and contradictory data helped me to distinguish cohesive and relevant themes with which to frame the project.

Confirming evidence satisfies many research demands. It establishes that the research question fits into what is normally understood about the topic - in this case safety as it relates to education - and then refines the study with techniques and approaches from related studies. As data are gathered, distilled, and interpreted, secondary literature searches clarify ideas. The presence of sufficient confirming evidence may justify strong claims.

The search for contradictory evidence adds important dimensions to a research project. Confirmation suggests; contradiction raises doubts. Confirming data may reinforce a tentative theoretical framework or discussion of implications with augmenting information. Contradictory evidence can challenge the validity of research by introducing new issues. Contradiction makes another useful contribution: if, in addition to good supportive evidence a researcher can justifiably claim that disconfirming evidence is unlikely to be found, the supporting evidence becomes more reliable(12). The absence of disconfirming evidence can strengthen claims made about the data.

It seemed unwise, in a study such as mine, to rely solely on obtaining adequate confirming evidence where many of the basic terms of reference are embedded in assumption. A thorough search which failed to produce contradictory evidence or which produced findings able to contradict null perspectives(13), might improve the credibility of implications suggested at the end of the thesis. One example of how this worked might be helpful.

Data about risk, emotion, intensity, stimulation, power, ethics, motivation, relationship, roles, and social dynamics slowly started to gel midway through the study, but I couldn't get a coherent idea from the mix of concepts. I revisited my path through the research, using the tools of confirming and disconfirming evidence to look for clues about anything I might have overlooked. I returned to an uncomfortable conversation early in my study when a senior researcher suggested that 'threat' should be taken more seriously than 'safety' as catalytic precondition for learning. I had dismissed the idea at the time. Using the tensions between kinds of evidence, I reversed the issues of safety into a different kind of question: could safety ever interfere with learning? Or: could the absence of safety ever be efficacious for learning? I found no defensible evidence to support a claim that either threat or an absence of safety could support learning which is uncontaminated by the negative effects of an unsafe process. I did not adjust my definitions of learning to include that which is damaging to the learner.

All of the issues identified through the literature search and then raised, investigated, and proposed throughout the project are open to challenge because the research questions seem to be inquiring into several implicit assumptions which have not been scrutinized in this way before. I am more confident about conclusions drawn from the study because the exploration of ideas continually included the consideration of alternative possibilities. While key confirming evidence is cited throughout the thesis, an increasing absence of contradiction is an invisible strength behind many of the findings.

Fundamental elements which were linked during preliminary searches into safety and learning were grouped into three sections: the learning context, learning relationships, and some processes of learning. First, data about the learning context introduce concepts about education, the social climate, and issues of power and control.

The Learning Context

The learning context provides a sense of location as well as of process. Education is defined through a summary of perspectives which emerged during the study. The social dimension of climate and the impact of power and control dynamics on climate and relationships are discussed.

Education

The goals of education form one of the underlying paradoxes of the study. The work of Shor & Friere (1987) and Illich (1971) notwithstanding, most education systems tend to share similar organizational features which define the relationships among/between teacher, learner, and content in hierarchical and political ways. This is an odd fact, considering the diversity of theories about the nature and aims of education. Scholars traditionally talk about aims of education and theories of learning. Perhaps an easier way to resolve some of the contradictory ideas about how education is typically understood might be if discourse was framed as theories of education and aims of learning.

The purpose of describing education was to set the framework for discussions about teaching and learning, not to begin a new debate. My own assumptions about education suggested that contextual and relational factors may be of crucial importance if the objective of teaching is to assist learners to learn. But current popular images of education seemed to suggest that learning organization are founded on bases of content delivery. Vallance (1985) explained that "what may not be evident to educational planners is the extent to which an emphasis on content limits our conception of what education can be" (p. 202).

Speaking of education in terms of possibilities, Smith (1982) called education "the dynamic field of social practice" (p. 9), which Courtney (1986) reframed as "a species of moral and social interventions" (p. 162). Jarvis (1992) continued that the social intervention of education should be specifically directed towards learning, but that 'learning' is "either part of the formal educational structure or is lost in the process of everyday life in informal and incidental experiences" (p. 5). Crittenden (1994) added that it is "characteristic of education to regard [knowledge] as being valuable...as a significant part of the good for human beings" (p. 294). Typically, educators hold power and authority over the curriculum, process, and evaluation which create the learning context; "education seeks to control learning in some way" (Jarvis, 1992, p. 236). When educators hold such power over content and control the social climate, they must also hold a large share of the responsibility for the learning experiences of the student.

Climate: the Social Dimension

Learning is constrained by the sociocultural milieu into which individuals are born, it is directed through pressures exerted by social structures, and it is subject to control by the power elites. Learning stems from the experiences of living in society, but paradoxically, there would be no society without people learning(14).

Within education, within both the infrastructure and the curriculum, the social context is the medium for learning. "By social context we mean the entire spectrum of roles, responses, expectations, and interaction between students and teachers, and among students. The educational process cannot be separated from its social context" (Rubenson, 1982, p.60). Vygotskii's (1978) research shows that the individual learns through social interactions framed by context and focused through content. According to Tiberias and Billson (1991), "the social context is inherent in every teaching situation..." (p. 68).

The communicative social nature of learning "requires a climate of mutual trust and teamwork in which people feel accepted and free to disagree and take risks" (Smith, 1982, p. 49) because the climate can offer the emotional and physical support for learning (Kidd, 1975; Apps, 1981). But the atmosphere which characterizes a given social context is created by the dynamics among individual members. "The process of learning is located at the interface of people's biography and the sociocultural milieu in which they live, for it is at this intersection that experiences occur (Jarvis, 1992, p. 17). The fundamental dynamic of a social group is the allocation of power, control, and responsibility. Interconnectivity between group dynamics, relationship, and learning is continually mediated by issues of power. McIntyre (1993) concludes: "it should be therefore a priority for...researchers to begin to specify context as a major determinant of adult learning" (p. 94).

Ideally(15), dynamics begin as the responsibility of the organization and the educator and then shift to become the responsibility of the learners. Adams (1975) observed that "The group soon warmed to talking without a [teacher]; they had become frank with each other, more deeply involved" (p. 45). Cuban (1993) wrote about content as though it were the catalyst for relationship: "at the heart of [education] is the personal relationship between the teacher and students that develops over matters of content" (p. 184). Maclean (1987) is specific in saying that "learning is enhanced in a group setting which allows for the interplay of ideas and hence the potential for 'building' on the combined resources of the group...[and]...when the learning climate fosters self-esteem, interdependence, freedom of expression, acceptance of differences, and freedom to make mistakes" (P. 129). If the climate of education forms the foundation for teaching and learning, issues of power and control affect the development of relationships because power and control are unevenly distributed by the nature of education.

Power and Control

Learning can never be dissociated from power relationships in the social context(16)

Issues of power and control affected every element of this thesis project. The features of social groupings were characterized by four questions: (1) who controls social process and cultural status, (2) who has how much power, (3) how is power distributed, and (4) how is responsibility shared?

In the conventional concept of organized education(17) power is skewed by a relationship of deference between teacher and learner(18). Program participants surrender degrees of personal power and aspects of relational control, supposedly in order to accomplish the greater purpose of maximizing learning outcomes. Ideally moral leadership, ethical conduct, content-expertise, and teaching skills combine in an educator to not only justify the learners' entering into such a submissive position but also to facilitate the extending of program leadership to the learner. A skilled educational leader recognizes the importance of each person developing power and control over their own knowledge (Gagne, 1974; Griffith, 1987; Gestrelius, 1995). Griffith (1987) defines a healthy and safe level of power and control as that which enhances "the ability to do"; it is not a matter of "power over or power with" (p. 59). Learners need to leave programs not only with content-specific advancement but also with the enhanced sense of agency which is stimulated through personal awareness and growth.

Learning Relationships

Context, climate, and social dynamics of power and control form the foundation for the learning relationships of education. These are not discreet features but are interactive conditions which develop according to the relational skills of each person.

Teachers

Teaching is about influence(19).

In the cultures of learning and education, the word 'teacher' is charged with a complexity of meanings. Profiles of teachers convey status, power, and control over knowledge acquisition/ production throughout society. Lindeman (1956) describes the stereotypical educator as "the oracle who speaks from the platform of authority" (p. 160). Learner experiences with this type of educator seem "to cause the individual to distrust [his/her] own experience and to stifle significant learning. Hence I have come to feel that the outcomes of teaching are either unimportant or hurtful" (Rogers, 1969, p. 277). From these perspectives, teaching is a problematic activity.

Schon (1987) interprets Rogers' underlying intentions by centering the discussion on the ideal role for teaching, where learners strive to know how to learn and teachers are alongside to help them. Schon claims that Rogers has "not lost interest in being a teacher, but that he has reframed teaching in a way that gives central importance to his own role as a learner. He elicits self-discovery in others, first by modelling for others, as a learner, the open expression of his own reflections (however absurd they may seem) and then, when others criticize him, by refusing to become defensive. He believes that the very expression of thoughts and feelings usually withheld, manifestly divergent from one another, has the potential to promote self-discovery (p. 92)."

Lukmann (1997) extends this point of view by suggesting a shift from trying to know how to teach to one of understanding what makes learning possible.

Educators model for learners how learning should be approached (Bandura, 1986). "How we teach is what we teach" stresses Cuban (1993, p. 185). Boud (1987) acknowledges the influence of teachers on learners and on the learning climate, but cautions that a singular emphasis on 'modelling' overlooks the dilemma of modelling one's teaching practice on the skills of a remembered teacher which may leave one unprepared for the demands of an educational culture very different from that in which one learned (p. 222).

Tom (1984) picks up the relational themes of the social context: "teaching...is a dynamic activity...a relationship between teacher and student" (p.11) in which, writes Eisner (1991), teaching works as an artistic mediative function between content and learner (p. 11). According to Rogers (1969), in order to fulfill that function, the teacher "does not teach, but serves" (p. 92).

Tom (1984) asserts that therefore no objectively effective and instrumentally based teaching skills are assignable because "the typical teaching problem may well have multiple appropriate solutions and because teacher-student influence is both bidirectional and mediated by a variety of factors...teaching is normative and situational"(p. 147).; "teaching is not a form of practice under the firm control of the practitioner" (p. 73). Describing the act of teaching, Eisner (1979) writes that "teaching is a form of human action in which many of the ends achieved are emergent - that is to say, found in the course of interaction with students rather than preconceived and efficiently attained" (p. 154).

Schon (1987) describes the functions of a teacher to be: " (1) to ask what the student wants the project to be...conveying the message that personal preferences ought to be expressed and used to guide the project; (2) to encourage [the student] to try to produce what she likes... 'opening up the possibilities'; (3) to [be able to] judge the results of her work in terms of her effectiveness in 'realizing those qualities she defined' " (p. 152). Caffarella (1988) rounds out general views about teaching by expressing a dichotomy consistent with many teaching organizations: "teachers...have two primary roles: to be content specialists and/or facilitators of the learning process" (p.108). Berkowitz (1997) focuses on the effect of teaching: "the best way to document how well you teach is to show how effectively students learn" (p. 16). It appears that there is one common thread: teaching exists for learning. This suggests one common dilemma: whose definition of learning?

Learners/Learning

Oddly, the definition and manner of use of the term learning has caused relatively little controversy among theorists...the tendency is to allow the socially accepted meaning to prevail. The difficulties that do emerge in usage show up when theoretical processes and mechanisms for explaining learning are proposed(20).

Over the years nearly every conceivable form of [learning] theory has been seriously proposed...theorizing about learning is an exercise in generalization and often can be as polemical as it seeks to be empirical (21).

I began to study learning through a lens of content delivery or knowledge acquisition because that was the dominant model of education. As I confirmed that 'learning' is a labyrinth of processes and outcomes which cannot easily be defined, I shifted the study to consider which approaches facilitate learning by helping learners 'learn how to learn'. In this approach to learning, people take what they know as the framework from which to work with what they don't know in order to develop, to grow (Kidd, 1973; Smith, 1982; Brookfield, 1986).

I reframed learning in terms of experience(22), education as a way to achieve purposive learning by organizing and managing experiences, and formal education as adding an organizational context and the presumption of an educator-learner relationship. From a similar perspective, Osborne (1985) wrote that learning is

a change in our being-in-the-world, in our lived experience, which may include all aspects of our being but especially our perceptual, symbolic, and emotional processes. It is more that an intellectual change. It can disrupt the inertia of our prevailing state of consciousness. A change in world view can also be described as a change in attitude or disposition with accompanying feeling states. It is the way we perceive/feel/think about our world/s (p.196).

Rogers (1969) calls this "self-appropriated learning" (p. 277). Evidence that experience has

become learning is found through a "demonstrable new capacity" in any aspect of living (Griffin, 1983, p. 13).

Education, then, is an intentional ordering of experiences to achieve specific kinds of learning. Learner experiences occur in relationship with an 'educator' (and the educator's area-of-expertise content). This relationship is designed to maximize particular kinds of desired learning and usually includes more than one learner, adding the element of a group dynamic within the educational context. In both delivery and evaluation, education tends to focus on the planned curriculum. Consequently, a myriad of hidden learning outcomes are overlooked (Cuban, 1993). Echoing the earlier comments about the gap between the curriculum offered, the teaching which is presented, and the learning which occurs, Dewey (1938) points out the "pedagogical fallacy" of presuming that a person's only learning is what's being studied (p. 48). Maling and Keepes (1985) agree that "students learn what they are exposed to rather than what curriculum developers necessarily intended that they should learn" (p. 267).

Purposive learning usually requires a milieu for learners to imagine change, to strengthen the ability to learn how to learn, to develop persistent effort and goodwill, to acquire information with which to work, and to experience the opportunity of evaluating their perspectives. According to Pine and Horne (1969), learners are not 'taught', but through their relationship with a teacher, become motivated to learn. Much of the value attached to learning is derived from the expectation that learning will effect some change in one's skills, attitudes, understanding, capacity, attributes etc. Definitions imply that learning endures. Enduring implies life changing.

I investigated what seemed to be happening for learners when learning seemed to be (or not to be) taking place. I wondered if it mattered whether or not the learning was about emotive issues like fear and anger or about more instrumental issues like mechanics and construction? I decided that the focus questions chosen for the study would need to accept differences among learners and ask what pre-conditional aspects of learning might influence learning experiences. I became increasingly interested in the ecology of education when I realized that learning is a social experience, and compared what elements of a 'learning' climate and a social dynamic might be. My interest became centred on the interplay between teaching and learning. I could see that issues of power, trust, communication, goodwill, risk, ethics, commitment, attention, motivation, and safety were significant factors of those relationships. As my study moved towards understanding the social dynamic, safety continued to emerge as a potential 'umbrella' concept.

Social Dynamic/Group Dynamic

How complex social dynamics are if course tutours take seriously

what students are experiencing(23).

A diffused social group becomes defined as a group dynamic when program participants move through introductions to the work of learning. The group dynamic will develop with or without guidance from the educator but, because of the pivotal importance of relationships to successful learning outcomes, educators have a fundamental responsibility to lead group development (Griffin, 1987; Hodgson & Reynolds, 1987; Hare, 1992; Hyde, 1992). The educator has most of the power and responsibility to influence what sort of dynamic emerges: "[as the teacher] the atmosphere you create during the first hour of a class often determines the tone for the rest of the class sessions" (Apps, 1991, p. 78; Knowles, 1980, p. 224). "The behaviour of the instructor is, without a doubt, the single most potent force in establishing a social climate" (Knowles, 1980, p. 225). Tom (1994) suggests that educators create a "frame of the deliberate relationship".

A learning community "emerges from mutual communication, meaningful work, and empowering methods" (Shor, 1992, p. 259). It is important that individual learners are capable of sharing group goals (Hayes, 1989). There needs to be a "sense of inviting a range of voices and styles of communication within it" (Burbules, 1993, p. 7).

Tiberias and Billson (1991) suggest that content expertise, while essential, is only one ability educators must bring to their class: "The most effective leaders pay as much attention to resolving conflict, ensuring even participation, and testing group sentiment as they do to planning, keeping the group on task, and evaluating productivity" (p. 77). A relationship which protects people from each other decreases the potential for learning (Schon, 1987, p. 299). Educators need to create a context in which conflict is engaged free of coercion (Mecke, 1990, p. 207). The optimal learning site depends on finding common ground and creating non-compromising relational processes which establish a safe context in which challenges and conflicts can be skillfully explored. Burbules (1993) concludes: "without differences to play against, learning is impossible (p. 26).

Robertson (1987) suggests that "through identifying the similarities and differences in our perceptions of each other, we can encounter the boundaries of our own perceptions and reach the point where learning may begin" (p. 85). The explicitly differentiated, negotiated, and supportively constructed social dynamic creates a context in which judgement and moral reasoning can be developed (Burbules, 1993, p. 70). Such a dynamic can encourage a practice of the art of heteroglossia(24) - the ability to "honour difference while at the same time finding common ground" (Fenstermacher, 1994, p. 5). Eisner (1991) goes further by asserting that the "genuinely good schools do not diminish individual differences, [they] expand them" (p. 17). Underscoring a fundamental tension, Burbules (1993) writes "we need to be similar enough for communication to happen, but different enough to make it worthwhile" (p. 31).

Because a positive social dynamic increases the complexity and stability of learning (Long, 1983, p. 239; Mezirow, 1996, p. 170), educators need to acknowledge that a "keener awareness of group processes can enhance teaching effectiveness through improving participation levels, increasing individual and group motivation, stimulating enthusiasm, and facilitating communication" (Billson & Tiberias, 1991, p. 88). Group processes develop either explicitly or implicitly according to how the 'rules' of conduct are conveyed, constructed, and maintained.

Implicit/explicit process.

Normative processes for behaviour develop whenever a number of individuals come together as a group. The extent to which each person's values may be included depends on whether group processes are inclusive; inclusivity depends on how group norms are developed. Explicit and implicit processes serve different and complimentary functions.

Implicit rules of conduct are the result of once explicitly negotiated understandings becoming integrated into the social dynamic and are therefore internally controlling and automatic. When group membership remains unchanged and group goals remain stable, implicit process may be efficient and productive as long as the option to adjust the rules is also embedded in the process. Echoing Minnich, Reinharz (1985) suggests that "since interest-free knowledge is logically impossible, we should feel free to substitute explicit interests for implicit ones" (p. 17).

The implicit process blocks change when rules and information are hidden so that power and responsibility may not be shared because if differences or misunderstandings cannot be approached, relationships cannot change(25). A strong sense of community develops in contexts where learners are able to explore their implicit assumptions and reflections in subjective as well as collective ways.

An explicit process is important (Griffin, 1987, p. 209; Hyde, 1992, p. 179) because making criteria explicit "helps to map the paths" (Peters, 1973, p. 28). "Mapping" makes the details and boundaries obvious, thereby providing choices of action. Guiding protocols and

procedures may even be more efficient if clearly stated (Gestrelius, 1995, p. 137). The authentically explicit process is experienced not as rule-bound authority (Burbules, 1993, p. 82) but as a set of firm but negotiable guidelines. Sork & Welock also suggest (1992) that making process explicit is also an ethical action (p. 117).

The process of explicitly negotiating collective guidelines for interacting offers each person an equal opportunity to be both socially safe and socially skillful; communication skills may therefore need to be screened for or taught explicitly at the beginning of a program (Hayes, 1989, p. 60). The responsible educator needs to establish and maintain both an explicit process and an explicit awareness of content (Davies, 1987, p. 46). Hare (1993a) elaborates: "what we choose to teach more directly...will constitute an important part of the resources [learners] will have available to bring to the problems and issues they will face" (p. 11). Where a 'clarifying or negotiating of process' is explicit then relational, communicative, and critical skills are developed(26). Experience which is open to critical reflection has the potential to become meaningful and useful.

The thesis project identified commitment as a key learner characteristic. Making ideas, feelings, and cultural norms explicit is to share power, information, and process - thereby increasing learner investment and involvement. For learners to explicitly "name in their own way the processes they are experiencing, is an empowering skill" (Griffin, 1987) which helps them transform the ascribed needs of a program to their own felt needs.

Group norms

keep safety issues safe

develop the group's dialogic language

seek common ground

increase relational and communication skills

The negotiating of group norms is a key area for explicit approaches because the cultural rules by which a group functions determine how relationship develops, power is distributed, and safety procured. There are subtle but significant differences between the idea of negotiated guidelines for the development of relationship among individuals, and the concept of rules or codes of conduct. Rules and codes sound imposed by external power. The process of negotiation not only shares power but also builds power and responsibility within the negotiating group(27). Negotiation is an intragroup activity, engaged anew with each new group on the arrival of a new participant.

The research project identifies many safety issues(28) which need to be negotiated as group norms. If participants have basic relational skills, the negotiation of group norms can be accomplished in a brief amount of time. If those skills are not present, then the capacity of the group to engage in learning together may be significantly limited. Schon (1987) continues: "building a relationship conducive to learning begins with the...establishment of a contract that sets expectations for the dialogue: what will [teacher] and student give to and get from each other? How will they hold each other accountable?" (p. 167). Hare (1993b) adds that explicit norms act as a "checklist to help cover important factors" (p. 97). Clear norms negotiated at the beginning are the foundation for the social dynamic (Carbines, 1989; Billion & Tiberias, 1991; Cervero & Wilson, 1995). What's more, learning occurs through the process of negotiation.